LEE MILLER

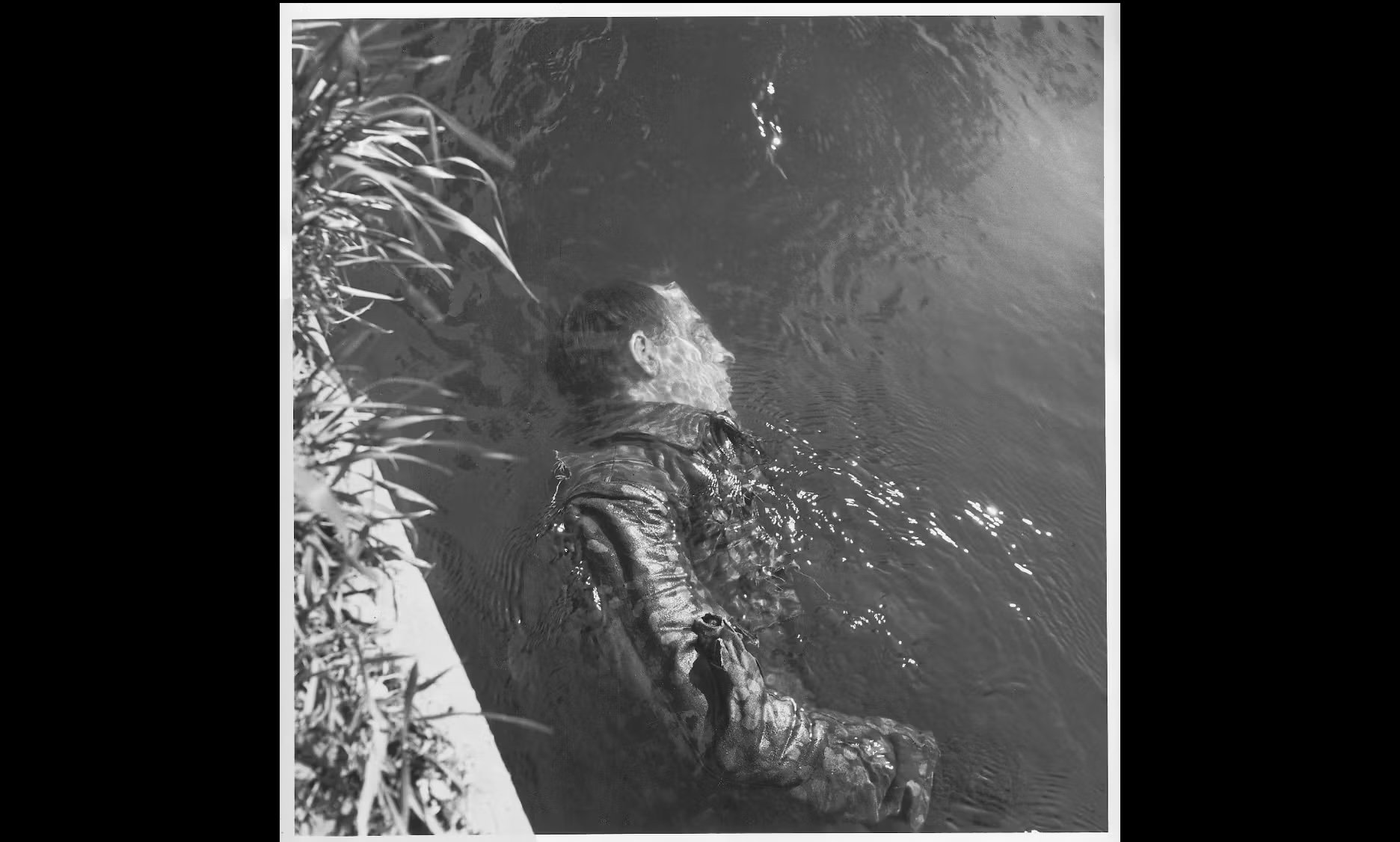

Dead SS Guard in Canal, Dachau, 1945

The body floats face-down in the canal, arms spread, military uniform sodden and heavy. The composition is almost serene. The water's surface reflects sky, the body seems weightless, suspended. It could be Ophelia, that romanticised image of beautiful death, woman driven mad by male violence, floating amongst flowers. Except this is a man. An SS officer. And the water is at Dachau concentration camp, liberated by American troops on 29 April 1945. Lee Miller photographed this the day she arrived, one of the few accredited women war correspondents at the front.

Miller had been a fashion model, photographed nude by Man Ray and others, her body circulated as aesthetic object for male consumption. Here she photographs a dead man, corpse as object, the gaze reversed. There's no heroism in this soldier's death. He's consumed, finished, stripped of power. The beauty of the composition sits uncomfortably against what he represents. SS officers at Dachau ran the death camp, oversaw atrocity daily. This man drowned in the infrastructure of his own violence, killed by liberating troops or camp prisoners in the chaos of liberation.

The photograph invokes baptism: water as purification, death and rebirth, cleansing of sin. But there's no resurrection here. The baptismal imagery suggests redemption then withholds it. He's just dead, floating in the canal, beyond judgment and beyond forgiveness. The theological framework the image conjures collapses under the weight of what happened at Dachau. Water doesn't cleanse this. Death doesn't absolve it.

Miller photographed the piles of bodies that same day, the emaciated survivors, the evidence of systematic murder. This image sits within that series. The SS officer's serenity exists in direct relation to others' suffering. Should we feel sympathy? The photograph seems to invite it through composition, through the peaceful floating form, through the Ophelia echo. Then it denies it through context: the uniform, the location, what we know. Miller forces us to notice our aesthetic response and question it.

The photograph tests our moral compass by making something beautiful from something monstrous. We're confronted with the gap between how death looks and what death means. The result is discomforting: a Nazi's corpse rendered with the visual grammar usually reserved for tragic heroines. Is this mockery? Rage? Or recognition that death is just death, regardless of who dies, and that aesthetic serenity has nothing to do with ethical reckoning?

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American photographer, model, and war correspondent. She documented the liberation of concentration camps including Dachau and Buchenwald in 1945, producing some of the most important photographic evidence of Nazi atrocity.

More on Miller: Lee Miller Archives | Imperial War Museum

Image credit:

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2025.