Lewis Morley

Christine Keeler, 1963

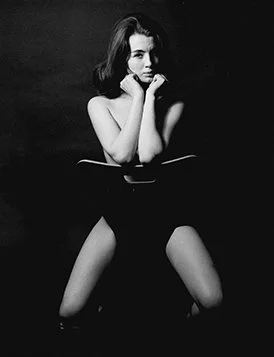

Christine Keeler sits astride a chair, arms crossed over her breasts, hands supporting her chin, staring directly at the camera. Her body is angled, legs spread around the chair's back, lower body dissolving into darkness. The pose suggests nudity without confirming it. The chair conceals and reveals simultaneously, creating geometric tension between vertical body and horizontal seat. This is provocation through withholding, sexuality constructed through denial.

The photograph was taken in June 1963 at Peter Cook's Establishment Club in Soho, the satirical heart of London's counterculture. Keeler had just become the most notorious woman in Britain. The Profumo Affair had detonated weeks earlier: John Profumo, Secretary of State for War, had lied to Parliament about his relationship with Keeler, a showgirl who was simultaneously involved with Yevgeny Ivanov, a Soviet naval attaché. The scandal combined sex, espionage, and establishment hypocrisy. When it broke, the government collapsed. Profumo resigned. Keeler became tabloid property.

Lewis Morley was commissioned to photograph her for the newspapers. The original plan was full nudity, but Keeler refused. Morley found a knockoff Arne Jacobsen chair, a modernist design icon, and Keeler posed astride it. The chair transformed what could have been exploitation into something closer to art. The Jacobsen reference situates the image within design culture, not just scandal photography. The pose became simultaneously more sexual and more controlled than full nudity would have permitted.

Keeler's gaze is direct, confrontational. She looks back at the camera, at Morley, at the viewer. This isn't passive objectification. There's defiance here, or perhaps exhaustion performing as defiance. By June 1963, she'd been consumed by media for months: working-class girl who'd slept with a Cabinet minister and a Russian spy, blamed for bringing down a government, caricatured as seductress and scapegoat. This photograph captures her at maximum exposure and maximum vulnerability, aware she's being looked at and returning the gaze with something between challenge and resignation.

The formal composition constructs this tension. Deep shadows break across the left side of her face, fracturing her direct stare. Her upper body is closed, defensive: elbows protecting breasts, hands supporting chin. Her lower body is open, legs spread around the chair. The contradiction is built into the pose. She's simultaneously guarded and exposed, withdrawn and available. The lower half of the image dissolves into blackness. Her legs and the chair legs fade into shadow, making her appear suspended, weightless, uncertain.

This photograph became the definitive image of the Profumo Scandal, reproduced endlessly, censored, parodied, iconographic. It escaped Keeler's control immediately. What began as a commissioned portrait became public property, shorthand for 1960s sex scandal, moral panic, establishment corruption. The image's power lies in how it holds contradictions: art and exploitation, empowerment and objectification, humanity and spectacle. Keeler is subject and object, active participant and passive specimen.

The scandal wasn't just about sex. It was about class. Keeler was working-class, accessing elite male spaces through her body, then destroyed for that transgression. Profumo lied to Parliament and resigned with honour. Ivanov disappeared back to Moscow. Stephen Ward, the society osteopath who introduced them, was prosecuted and died by suicide. Keeler went to prison for perjury in an unrelated case. The establishment protected itself. She carried the blame.

This photograph sits at the hinge between post-war austerity and 1960s permissiveness. In 1963, Britain was transitioning from moral conservatism to sexual liberation, but the shift was incomplete. The image shocked because it arrived early, before the culture was ready. Later in the decade, this pose wouldn't register the same way. The photograph captures that transitional moment, when a woman's body could still be both scandalous and newsworthy, art object and moral threat.

Morley's use of light makes Keeler simultaneously hypervisible and invisible. She's tabloid fodder, consumed daily, but also erased as a person. The shadows acknowledge this: she's present but disappearing, solid but ghostly, awaiting judgment. Not specimen or muse or victim, but all three at once. The photograph doesn't resolve the tension between these readings. It holds them, suspended in darkness, staring back.

Lewis Morley (1925-2013) was a British photographer known for portraiture and theatrical photography. His image of Christine Keeler became one of the most iconic photographs of the 1960s, defining how the Profumo Affair was visually remembered.

More on Morley: National Portrait Gallery | Victoria and Albert Museum